Don McCullin has visited war zones across the world in his 60 year career

A major retrospective of one of the world’s most acclaimed war photographers has opened at London’s Tate Britain. Don McCullin has spent 60 years photographing the impact of conflict, poverty and deprivation on humans across the world.

His career began in the 1950s when he sent a photograph from his native North London to The Observer newspaper. The Guvnors in Their Sunday Suits, a photo he’d taken of his friends stood in a derelict, bombed-out building, proved a hit with newspaper bosses. The Observer asked if he could take more photographs like that and he agreed.

Beginning by capturing life in poverty-stricken areas of London, McCullin soon ventured to Germany as the Berlin Wall was being erected. The Observer was uninterested in the story, but that didn’t stop him from going there to capture what would become a defining moment of the 20th century.

“Photography isn’t about just pushing that button,” he said in 2016 in an interview with the Canon Professional Network. “It’s about the experience of being there. I bring to my photography the principles of my mind and what I’m trying to do. I’m bringing the direction of who I am and what I’ve seen. I’m bringing my identity to it with my printing and my composition.”

His first experience of photographing conflict came in 1964 when he was asked to visit Cyprus during the civil war. It was here that he began to take photos of the dead, the dying and the grieving in what he described as an “ethnic cleansing” of the Turkish population by Greek Cypriot forces

By 1966, McCullin had begun working as an overseas correspondent for The Sunday Times Magazine, a position he held until 1984. He travelled to Biafra in 1968 where the secessionist state was being blockaded by Nigeria, leading to mass starvation of the population. He took images of malnourished women trying to feed their skeletal children with swollen stomachs, as dead bodies lay rotting on the ground. In an interview with Jiang Rong in 2006, he said he wanted readers to look at these images and think: “Why am I looking at these terrible images, like a child starving, in a world where there is too much food in the West?”

During the 1970s, he travelled to war zones in Northern Ireland, Vietnam and Cambodia – where he was hit by a mortar shell, which killed a Cambodian paratrooper. Despite being injured, he carried on taking photographs, including of the dying soldier who had been hit by the same shell.

McCullin recalled the moment in his 2002 autobiography, Unreasonable Behaviour.“We had shared the fragmentation, but he had taken most of it in the stomach … Minutes later, I noticed he was lying down again, his feet drumming too perfectly with every motion of the lorry. I knew that he had gone. It could so easily have been my dead corpse rattling. I thought, he’s gone instead of me.”

By 1976, he had ventured to the Middle East to document fighting between Christian and Muslim militias in Beirut. He captured the scene in Karantina, a predominantly Palestinian district of Beirut, where hundreds of people, mainly Muslims, were massacred. In one horrific moment, he saw young Christian men celebrating as a teenage Palestinian girl lay dead in a puddle of rain in the street. Unsure whether his own life was in danger, McCullin began to turn away until he was called over by one of those celebrating. “The boy called over to me. ‘Hey, mistah! mistah! Come take photo.’ I was still frightened but I shot off two frames quickly,” he wrote in his autobiography.

McCullin returned to Lebanon in 1982 during the Israeli invasion. He later described seeing horrendous crimes against humanity as the Israelis surrounded refugee camps to prevent people from fleeing while Christian Phalangists carried out massacres.

In the 1990s, having left The Sunday Times Magazine, he was seconded to Saddam Hussein-controlled Iraq by The Independent. In the aftermath of Iraq’s defeat in the Gulf War in 1991, the photographer travelled to the north of the country where he witnessed Hussein’s suppression of the Kurdish people.

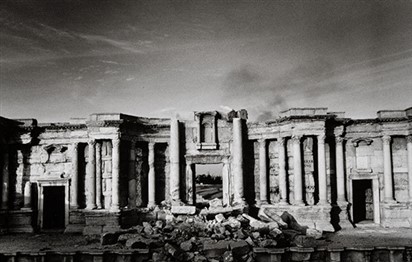

Most recently, he visited Syria to photograph the destruction left by ISIS. A photograph from 2017 shows the ruins left of the theatre in the Roman city of Palmyra, a world heritage site. In the same year he was knighted in the New Year Honours for services to photography.

The exhibition, which features over 250 photographs, is accompanied by McCullin’s commentaries on the scenes he witnessed. He printed all his photographs himself in his darkroom.

Now aged 83, he spends most of his time photographing landscapes in rural Britain. He says he has “sentenced himself to peace”. But his vast collection of ongoing conflict proves that war will never be over.

The exhibition runs until May 6 at Tate Britain, Westminster, London

www.thenational.ae