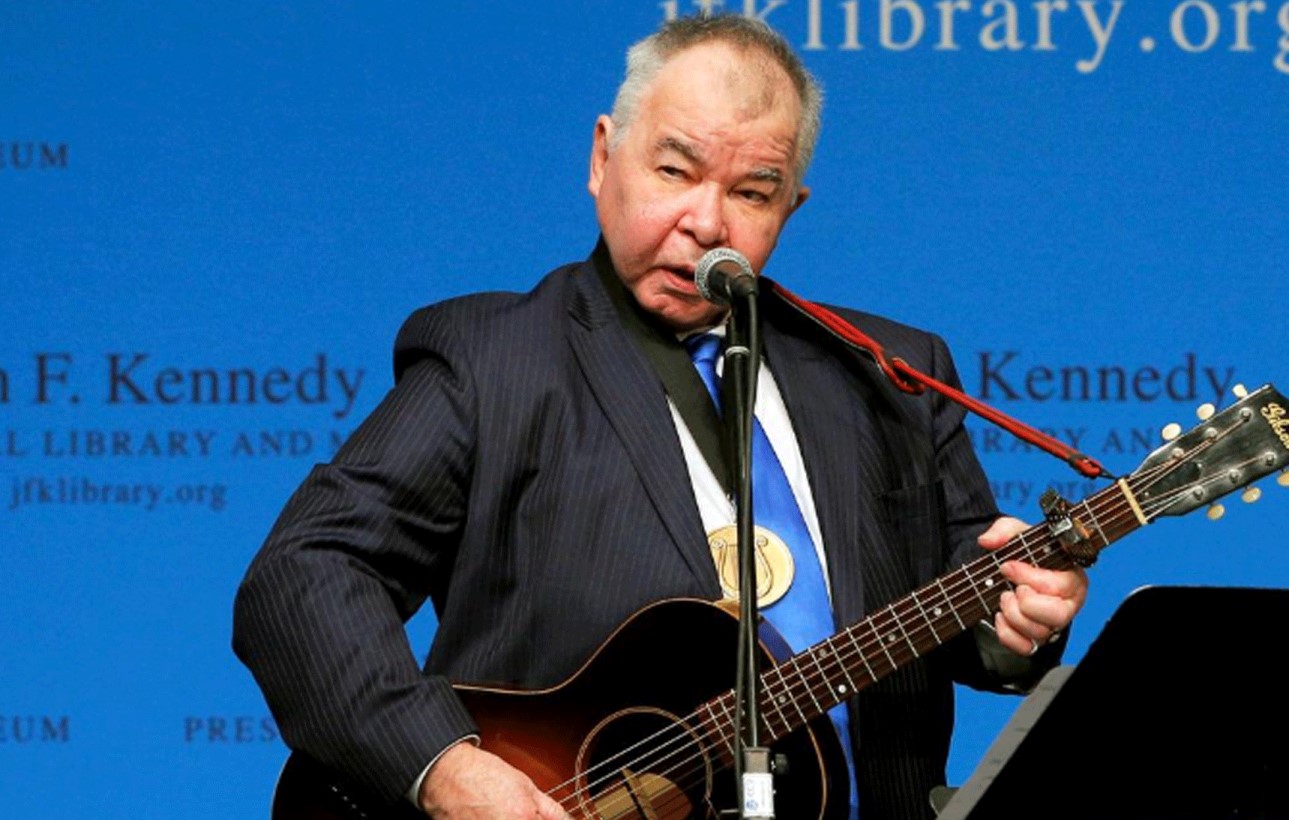

Grammy-winning singer John Prine, who wrote his early songs in his head while delivering mail and later emerged from Chicago’s folk revival scene in the 1970s to become one of the most influential songwriters of his generation, died on Tuesday. He was 73.

Prine was hospitalized in Nashville on March 26 suffering from symptoms of COVID-19, the respiratory disease caused by the novel coronavirus, according to his wife, Fiona Whelan Prine, who was also his manager.

“We join the world in mourning the passing of revered country and folk singer/songwriter John Prine,” the Recording Academy said in a written statement.

“Widely lauded as one of the most influential songwriters of his generation, John’s impact will continue to inspire musicians for years to come. We send our deepest condolences to his loved ones.”

A publicist for Prine confirmed his death due to complications from COVID-19 at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in his adopted hometown of Nashville.

Born in Chicago on October 10, 1946, to William Prine and Verna Hamm, both originally of Kentucky, Prine was taught by his older brother David to play guitar at the age of 14 and attended music classes at the Old Town School of Folk Music.

After graduating from high school in suburban Maywood, Illinois, Prine worked as a mail carrier for five years, performing in Chicago clubs in the evenings at occasional “open mic” nights.

He would say later that some of his best-known early songs were written while he walked the streets of Chicago delivering mail.

“I likened the mail route to being in a library without any books. You just had time to be quiet and think, and that’s where I would come up with a lot of songs. If the song was any good I could remember it later and write it down,” Prine told the Chicago Tribune in a 2010 interview.

He was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1966, stationed in Germany during the Vietnam War, before returning home to dedicate himself to music and establishing himself as a leading member of Chicago’s folk revival scene.

Singer-songwriter Kris Kristofferson fatefully saw Prine performing at the Earl of Old Town club, leading to Prine’s signing with Atlantic Records and self-titled debut album, released in 1971.

That album, widely praised by critics, contained several songs that would become staples of Prine’s catalog.

They included “Angel from Montgomery,” about a woman wishing for deliverance from her unfulfilling life, “Paradise,” about a Kentucky town devastated by strip mining, and “Sam Stone,” chronicling the downward spiral of a drug-addicted Vietnam War veteran and containing the oft-quoted refrain: “There’s a hole in daddy’s arm where all the money goes, Jesus Christ died for nothin I suppose.”

The songs have since each been covered dozens of times by other artists.

DYLAN COMPARISONS

His early songwriting style earned comparisons with no less than folk great Bob Dylan, who later called Prine one of his favorites.

“Prine’s stuff is pure Proustian existentialism. Midwestern mindtrips to the nth degree. And he writes beautiful songs,” Dylan told the Huffington Post in 2009.

Prine released a string of albums in the 1970s, winning larger audiences and critical acclaim as his music stretched from folk to country to Americana, often infused with a sense of humor.

In the 1980s, fed up with the recording industry, he started his own label, Oh Boy Records, releasing albums under that imprint for the next several decades.

He won his first Grammy Award in 1991, Best Contemporary Folk Album, for “The Missing Years.” He would win a second Grammy in the same category in 2005 for “Fair and Square.” In December 2019, the Recording Academy honored him with a lifetime achievement award.

Prine survived squamous cell cancer in 1998, undergoing surgery to his neck and tongue that left his voice with an even deeper, gravelly tone. In 2013, he was diagnosed with cancer in his left lung and had it removed.

Prine was able to find humor in his struggle with cancer, joking that it actually improved his voice. The same humor suffused much of his work, alongside its poignant commentary about the struggles and foibles of ordinary people.

“If I can make myself laugh about something I should be crying about, that’s pretty good,” he once said.

www.reuters.com