Coronavirus has forced many cultural institutions to shut their doors as governments attempt to control the spread of the virus, and in response, many have created virtual tours of their exhibits.

In the UAE, Sharjah’s Barjeel Art Foundation has opened a virtual exhibit that intended to highlight socially oriented artworks of 20th century Arab modernism, in addition to gender equality by presenting 126 works of art, with equal contributions from female and male artists.

Established 10 years ago by Emirati art collector Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, the foundation launched “A Century in Flux: Highlights from the Barjeel Art Foundation: Chapter II” as a research-driven exhibition at the Sharjah Art Museum.

Historically, and today, equal gender representation in museums and galleries remains a heated debate.

Female representation in art

Although in recent years several attempts have been made by international museums to exhibit solo retrospectives of female artists, they still remain underrepresented in cultural institutions. For instance, research shows that in European and North American galleries, only 13.7 percent of their represented living artists are female. Meanwhile, in the past decade, 14 percent of exhibits at 26 leading American museums focused on the artistry of women. And in London’s prominent arts institutions, only 22 percent of their solo shows were dedicated to women artists.

Read more: First Saudi Arabian thriller series ‘Whispers’ to debut on Netflix in June

At the new Barjeel exhibit, which is possibly the first in the region to display equal amounts of works by men and women, several of the female modernists on show were highly active in the 20th century and yet their trajectories haven’t been documented properly.

“We felt like it’s really a shame that these histories are not better known – they’re sort of erased. These women were written out of history and we wanted to discuss why this happened,” the Foundation’s curator Suheyla Takesh told Al Arabiya English.

Through the Barjeel team’s research, issues such as access to education and societal expectations were some of the key reasons why it was even difficult for a woman to pursue art as a career.

“If we go way back in history, the very first art school that was opened in the region was in Egypt in 1908. At that point, it was dominated by men. It wasn’t until 1939, that the Higher Institute of Fine Arts for Female Teachers opened in Egypt, becoming the first art academy for women.” continued Takesh. “A lot of times, for women back then, who were active in their youth, once they had a family, they would often stop practicing art professionally.”

Takesh’s comments serve as a reminder to the renowned art historian Linda Nochlin, who in 1971, famously asked through the title of her influential essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Female Artists?”

A fundamental reason for not achieving “greatness,” Nochlin argues, is because throughout history, immensely talented yet socially constrained female artists have been treated unfairly in terms of not receiving the same level of accessing education, support and public spaces as their male counterparts.

“The fault lies not in our stars, our hormones, our menstrual cycles, or our empty internal spaces, but in our institutions and our education,” wrote Nochlin. As the Barjeel exhibition proves, women not only reflected on what was happening around them in the world but also demonstrated detailed manual skills, working in weaving, ceramics, discarded materials, and light sculptures.

“When we were installing the exhibition, the idea of quality was actually never an issue. They were all really strong works,” commented Takesh. “What I noticed was how open and experimental women were with all kinds of medium.”

Meet the artists

To explore their little-known yet fascinating artistry, here are the stories of five women artists from the Arab world currently on display:

Safia Farhat, La Mariee, 1963, Tapestry, 172 x 100 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Safia Farhat, La Mariee, 1963, Tapestry, 172 x 100 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Safia Farhat (1924-2004)

Stepping into the exhibition, one’s gaze is instantly greeted with a large and colorful tapestry that depicts a woman, standing tall and strong, dressed in traditional bridal clothing. “La Mariée” (or “The Bride”) was executed by Tunisian artist Farhat in 1963, nearly a decade after her country gained independence from France.

Aside from experimenting artistically with glass and textiles, Farhat was politically intrepid, joining the women’s rights movement, encouraging the conservation of North African cultural heritage, in addition to launching the country’s first women’s magazine, called Faïza, in 1959.

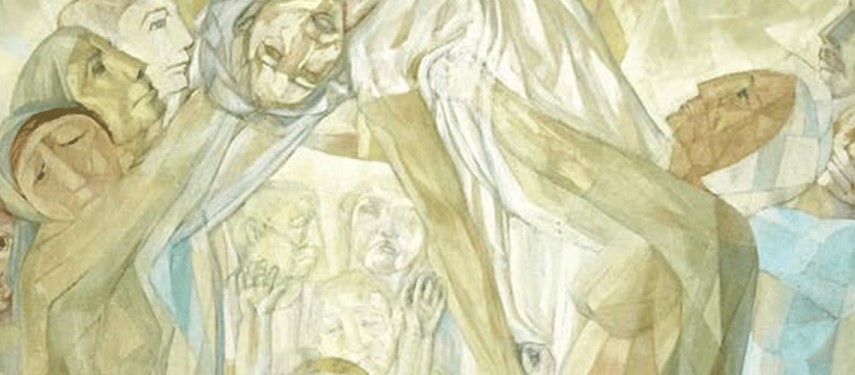

Leila Nseir, The Martyr (The Nation), 1978, Oil on canvas, 160 x 140 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Leila Nseir, The Martyr (The Nation), 1978, Oil on canvas, 160 x 140 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Leila Nseir (1941-present)

Featured a number of times in the exhibition is the Syrian painter Leila Nseir, who was born in the coastal city of Latakia in Syria and studied at the Faculty of Fine Arts in Cairo during the 1960s. A visually striking work of hers is “Motherhood”, a 1970, green-toned portrait of a seated woman with a noticeably elongated neck and upper body.

Meanwhile, “The Martyr” from 1978 is more socially engaged, reflecting the region’s instability at the time. For a heavy subject such as martyrdom, Nseir poetically uses light colors and depicts the grieving characters in a graceful manner. Takesh interestingly pointed out how the composition exudes a strong female presence.

Leila Nseir, Motherhood, 1970, Oil on canvas, 202 x 102 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Leila Nseir, Motherhood, 1970, Oil on canvas, 202 x 102 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

“Normally, martyrdom would really foreground the man as the hero. It’s either the man that’s portrayed or the martyr’s weeping wife,” she explained. “So, this is why this work is so unique, where we see a female martyr being carried by other women and children.”

Inji Efflatoun, Dreams of the Detainee, 1961, Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Inji Efflatoun, Dreams of the Detainee, 1961, Oil on canvas, 50 x 40 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Inji Efflatoun (1924-1989)

A prolific figure of Arab modernism is the Cairo-born painter and political activist Inji Efflatoun. An entire exhibition wing holds eleven of her poignant paintings. Coming from a well-to-do family, the French-speaking artist was influenced by European culture throughout her childhood. She made the surprising decision to study art in Cairo (instead of Paris), according to Takesh, “to get Egyptianized and reconnect with her roots.”

“My main desire was to reflect the ordinary Egyptian,” Efflatoun, who painted Egyptian rural scenes, once said in the 1940s. “To express the reality and dreams of the simple, crushed human beings who toil in deplorable conditions, with no rights, and no laws to protect them.”

Inji Efflatoun, Ezba (Farm), 1953, Oil on board, 47 x 63 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Inji Efflatoun, Ezba (Farm), 1953, Oil on board, 47 x 63 cm. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

It was in the 1950s when Efflatoun was imprisoned for her political activism that she would produce some of her finest pieces while confined, such as “Dreams of the Detainee” from 1961. Holding onto a jail bar, the female sitter looks away from the viewer and is serenely lost in thought.

Menhat Helmy, Outpatient Clinic, 1958, Oil on canvas, 66 x 80 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Menhat Helmy, Outpatient Clinic, 1958, Oil on canvas, 66 x 80 cm. Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Menhat Helmy (1925-2004)

Another fellow Egyptian artist is Menhat Helmy, whose diverse body of works recently came to light thanks to efforts made by her family (especially her grandson) to publicize her eventful career through the Internet and an informative Instagram account.

A student of London’s Slade School of Fine Arts, Helmy exhibited her works in Cairo’s art galleries during the 1960s and went through different artistic phases in her life, trying her hand with black-and-white etching and bold abstract painting.

However, as a keen observer of her surroundings, she is known for her unique imagery of Egyptians as seen in this exhibited artwork, “Outpatient Clinic”. In a way, the medical theme of this composition is as relevant today as it was back in 1958. “Helmy herself had a socialist perspective,” commented Takesh. “So, she painted a lot about the transformations of the education and healthcare system under Gamal Abdel Nasser in Egypt in the 1950s and 1960s.”

Vera Tamari, Palestinian Women at Work, 1979, Ceramic relief. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Vera Tamari, Palestinian Women at Work, 1979, Ceramic relief. (Image courtesy of Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah.)

Vera Tamari (1945-present)

Made of ceramics, the small and tactile “Palestinian Women at Work” was created by the Jerusalem-born artist and teacher Vera Tamari in 1979. Educated in Beirut, Florence and Oxford, Tamari grew up in an art-loving family and today, she remains active in her seventies, making conceptual installations and vibrant natural landscapes.

A pioneer of arts education in Palestine, Tamari introduced the fine arts program at Birzeit University, along with co-founding the university’s museum. In her formative years, Tamari (who opened the West Bank’s first ceramics studio in the 1970s) was drawn to using local materials, especially clay, producing sculptural paintings.

In this rare, detailed artwork, painted in turquoise and deep browns, she renders the embroidery on the workers’ dresses. “It has an unmistakable Palestinian character to it,” analyzed Takesh. “But at the same time, she’s being clever about making Palestinian art that is not in response to a political conflict necessarily and making something that just is – in it and of itself.”

english.alarabiya.net