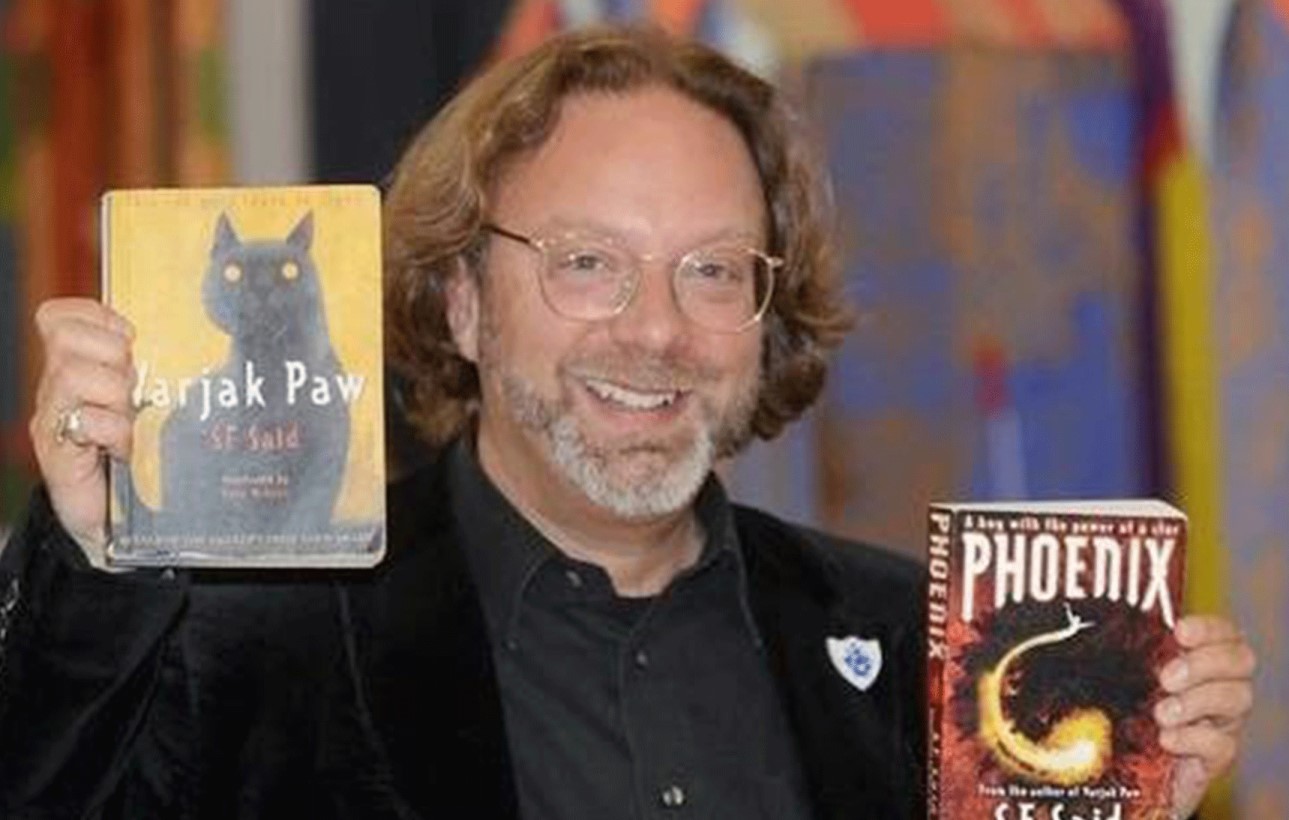

SF Said’s story joins works by Lauren Child, Anthony Horowitz, Michael Morpurgo, Onjali Rauf and Sita Brahmachari

In SF Said’s first work of children’s literature, Varjak Paw, the eponymous cat is just venturing out into the big, wide world. By rather appropriate contrast, the feline hero rendered by the author in The Book of Hopes, a collection of short stories published for children in the time of coronavirus, is living in close confinement.

The Naughtiest Cat I Have Ever Known is a 500-word tale by the Beirut-born Said that sits alongside 110 other contributions from leading children’s authors, poets and artists to provide, as the full title of the book describes, “words and pictures to comfort, inspire and entertain children in lockdown”.

Said’s cat in the short autobiographical story, named Monamy from the French “mon ami”, is not under restrictions imposed to contain the spread of Covid-19 but instead lives in the claustrophobic third-floor London flat that was the writer’s childhood home. Ultimately, Monamy performs a valiant leap that sends a pompous relative of Said’s packing. Before that feat, however, the cat is climbing the walls and tearing the place apart.

“I was thinking about myself as a child at a time when I felt very isolated in a way that I imagine kids in lockdown will be feeling everywhere,” Said told The National. “It was the appearance of this extraordinary, incredibly naughty cat that sent this explosion of activity and hope into my life,” he said.

“My mum was a single mum. I was an only child. She was quite protective and we lived in not the most salubrious bit of London. She didn’t really let me go out on my own until I was about 13, I think.”

The Book of Hopes has been launched as a free online offering by the National Literacy Trust in the UK, and will eventually be published as a gift book in the autumn by Bloomsbury in support of NHS Charities Together.

It is dedicated to: “The doctors, nurses, carers, porters, cleaners and everyone currently working in hospitals: you are the stuff that wild, heroic dreams are made of.”

The Hope Project was begun only a few weeks ago by the award-winning author of The Good Thieves, Katherine Rundell, who emailed some of the children’s writers and artists that she most admires, asking them to write or draw something that might make children “laugh or wonder or snort or smile”.

“The response was magnificent, which shouldn’t have surprised me, because children’s writers and illustrators are professional hunters of hope,” Ms Rundell said in the foreword.

“We seek it out, catching it in our nets, setting it down between the pages of a book and sending it out into the world,” she said.

The resulting stories, poems, essays and pictures are not all explicitly about hope but they each aim to create it through plastic-devouring caterpillars, doodles, revolting or beautiful poems, stories of space travel, new shoes and dragons – or true accounts of a cat, like that of SF Said’s.

He was just one of the many luminaries who wholeheartedly embraced the project, including Lauren Child, Onjali Rauf, Anthony Horowitz, Michael Morpurgo, Axel Scheffler, Jacqueline Wilson and Sita Brahmachari.

Said, who won the 2003 Smarties Prize for Children’s Literature for Varjak Paw, described the The Book of Hopes as a wonderful, inspiring idea and was thrilled to have been asked to contribute. “I tried to think what I could do,” he said. “I think that children’s literature is capable of expressing absolutely anything that any other kind of literature is capable of expressing. But one thing I think it is uniquely good at expressing is hope as a possibility.”

As the world looks for silver linings amid an avalanche of negatives produced by the coronavirus pandemic, it is Said’s own hope that children will discover or reconnect with the joys of reading – but also possibly take that pleasure one step further by creating their own written works.

“If you love reading as a kid, and that could be reading anything, that is the single best thing you can possibly do,” he explained.

“Move from reading to writing for pleasure or drawing for pleasure. It can be anything. Make videos for pleasure, animation. That is enormously powerful.”

Before the coronavirus outbreak, Said would regularly embark on school visits, talking to children about reading, writing and creativity. The closure of schools has stopped him from turning up in person but he has been using online video chats to reach out to pupils. It might not be exactly the same thing, he says, but the connection is still there.

“The fact that I was not in the room did not get in the way of the message being communicated,” he said. “I was really getting the sense that what they were getting from it was exactly that – the feeling they wanted to go and write their own stories now, and you could do that at any age.

“One thing I always try and get over to kids is that age is irrelevant to writing. [Those] guys can totally be writers right now. Just think about what you love and write something about that.”

The message that Said is sending now in his talks and his stories has come full circle because it was his own pet, Monamy, when he was a child that provided the inspiration for his own career as a children’s author.

“I remember writing stories about him at the time, making comics about him. I used to love drawing him,” the author said of his adored childhood cat. “I think whatever it is that you love – a pet, another person, another object, a sport… making something about the things you love can be an incredibly hopeful thing to do.”

The Book of Hopes begins with a particularly poignant drawing by Lauren Child of a little girl framed in the window of a house, all in monochrome, looking out at the vibrantly colourful birds perched in a tree just outside.

It serves as a powerful illustration of Said’s belief that the book might be a creative momentum to help its young, cooped-up readers find release, freedom and possibility. “Which I think we could all use a bit of now,” he says.

www.thenational.ae