The art world was in shock when the acclaimed French-Moroccan photographer and video artist Leila Alaoui was killed in a January 2016 terrorist attack at the Splendid Hotel and the nearby Cappuccino Café in Burkina Faso. The artist was shot while sitting in a vehicle outside the targeted locations and died three days later. She was only 33. A friend of hers recalled how, days before her departure, Alaoui told her, “Don’t worry, I have been to more dangerous places.”

By the time of her death, Alaoui had captivated audiences with her humane portraiture documenting — among other topics — the fragility of human life in refugee settlements in the Levant, the status-quo of women’s rights in Africa, and the grace exuded by members of local communities in traditional Moroccan cities. A courageous and socially committed artist, Alaoui was once described as giving “a voice to the voiceless.”

Born in Paris and raised in Marrakech, the New York-educated Alaoui was sensitive to her social surroundings and focused on using photography to highlight critical issues that Mediterranean communities face: particularly migration, displacement and identity. Alaoui was involved with a range of NGO-assigned photographic opportunities, including her collaboration with the Danish Refugee Council, for which she photographed displaced Syrian men, women, and children in Lebanon six years ago in a series called “Natreen (We Wait).”

Another significant work from her oeuvre is 2013’s “Crossings,” a three-channel video installation in which Alaoui humanized the struggles of sub-Saharan migrants making their way to Europe. Alaoui conducted extensive research for this six-minute project, talking to migrants, journalists, and activists to gain a better understanding of Morocco’s migration crisis.

On her deep interest in exploring this complex theme, Alaoui once reflected: “Throughout my adolescence in Morocco, stories of migrants drowning at sea became regular on the news. In my eyes, these stories were constant reminders of deep-rooted social injustice. My French-Moroccan identity gave me the privilege of crossing borders freely while others couldn’t.”

Always on the move, Alaoui spent the last days of her life working on an assignment commissioned by Amnesty International and UN Women — as part of the international “My Body My Rights” campaign — to photograph and share stories of women who triumphantly overcame abusive hardships in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso.

Alaoui’s reputation as an artist and activist strengthened as her works became (as they continue to be) widely showcased in exhibitions at notable venues including the Musée du Quai Branly and Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris, New York’s 1-54 Contemporary African Art Fair, the Marrakech Biennale, and Art Dubai. In addition, Alaoui’s photography was acquisitioned by major cultural institutions, including London’s British Museum and the Maison Européenne de la Photographie in Paris.

Currently paying homage to her photographic work is Casa Árabe — the reputable Madrid-based institution that was inaugurated in 2008 with the unique mission of linking Spain and the Arab world through diverse programming and cultural activities. For the first time in Spain — through the collaborative efforts of the Embassy of the Kingdom of Morocco in Spain, the Leila Alaoui Foundation, and the Musée Yves Saint Laurent in Marrakech, including Hélicon Axis — visitors are granted the opportunity to observe 30 photographs taken by Alaoui in an exhibition entitled “The Moroccans,” running through September 22 (although the Casa Árabe is closed throughout August).

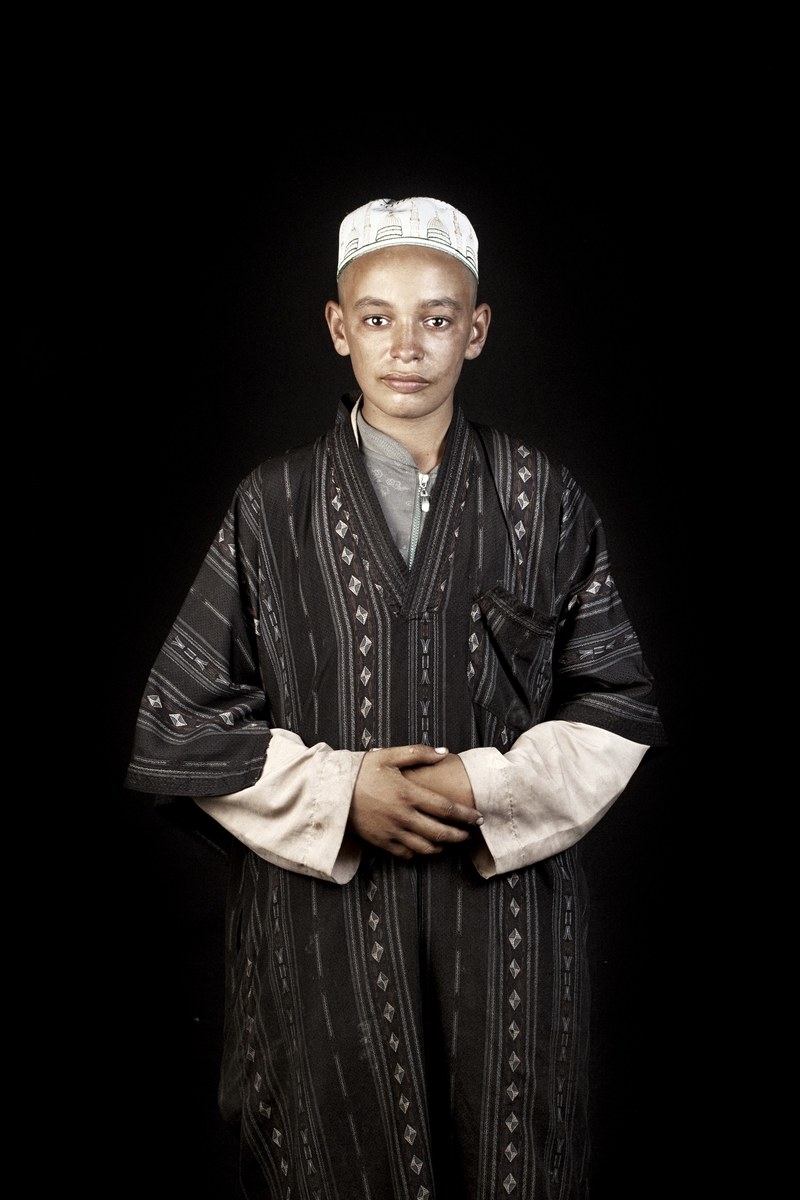

“The Moroccans” — shot between 2010 and 2014 — is a poignant exhibition. Alaoui travelled across Morocco, visiting rural towns and setting up a mobile studio in public markets, inviting men and women to come and be photographed in a formal manner. Young and old, from all walks of life, everyone was welcome inside Alaoui’s modest world.

The result is visually striking due to the neutral, pitch-black background, accentuating the often vibrant and elaborate attires of the sitters, and their penetrating, inescapable gazes. “Her models’ expressions, at once humble and powerful, are neither ‘Moroccan’ nor ‘African’; they are simply human,” the Paris-based writer and photographer Guillaume de Sardes, who curated the exhibition, wrote in the brochure. The sheer simplicity of Alaoui’s composition is a major part of what makes this particular series so iconic in the field of contemporary photography.

For this series, which also acts as an anthropological account, Alaoui was influenced by legendary photographer Robert Frank’s seminal photography book “The Americans” and Richard Avedon’s photographic series “In the American West.” In “The Americans” — published in the 1950s — Frank embarked on several road trips across America, reaching 30 states and documenting post-war American culture, touched by racism and consumerism. Avedon’s 1970s and 1980s portrait series defied stereotypes with his portrayal of ordinary individuals of the rural West — a region that was idealized in the American imagination. Evidently, Alaoui shared both photographers’ sense of adventure, composition style, and commitment to capturing hidden realities.

“She was trying to present these individuals from a pictorial point of view,” explained José Tono Martínez of the Spanish cultural management firm, Hélicon Axis, to Arab News. “She wanted to also present them with a lot of respect, like the portraits made by the great painters during the 15th and 16th centuries. She was not fond of the (Orientalist) point of view. If you see her pictures, you will see this sort of objective presentation, with a lot of dignity. These are not executives working in Rabat or Casablanca. She was interested in portraying a Morocco that was disappearing and she was conscious of that.”

Alaoui had previously shared the objective behind the series, and echoed Martinez’s insights: “Its images are an attempt to bear witness to the rich cultural and ethnic diversity of Morocco, an archival work on the aesthetics of disappearing traditions through contemporary digital photography.”

In her thoughtful artistry, Alaoui showed an admirable devotion to storytelling, even in the midst of violent settings, offering hope not just to future generations of photographers, but, in a way, to the region as well.

“She represents something very positive, which is what we need to demonstrate in front of non-Arabs in Europe,” said Nuria Medina García, the cultural programs coordinator at Casa Árabe. “She was cultivated and had a commitment to her society and intellectual tradition, embodying many positive values. For us, as an institution, it’s very important to give visibility to people like Leila, who really contradicts the many negative images that are coming from Arab countries at the current moment.”

https://www.arabnews.com