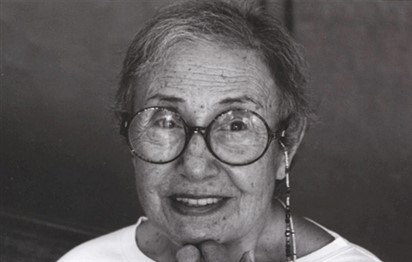

The painter, and daughter of Lebanon’s first president, created canvases of exquisite beauty

The Lebanese artist Huguette Caland has passed away in Beirut at the age of 88. A painter of extraordinary, luminous works, Caland became a model for artistic freedom and self-expression.

She was born into an important Lebanese family, and shocked her father — Bechara El Khoury, Lebanon’s first post-independence president — by marrying into a French-Lebanese line. It was the first of a number of times that Caland broke with tradition, though her most radical transformation would only come after the death of her father when, as her daughter Brigitte Caland says, “she felt free”.

Caland professionally came to art-making late, entering the American University of Berlin at the age of 30. But she did not hold back. After she nursed her father in his last days, in 1970, she decided she had fulfilled her obligation to her family. She left Beirut — and her husband and three children — for Paris. There, she spurned Western-style clothing, and instead chose a habit of kaftans, both as fashion statement and as painting smocks. Many of these robes are now exhibited as artworks in themselves, and they were also the catalyst for a brief foray into fashion: Pierre Cardin, inspired by them after she passed by his shop, also asked her to design a line for him.

In the 1980s, Caland moved to Los Angeles, where she built a house based on modernist ideas of openness and fluidity; its central courtyard also evoked her native Beirut. Her home was a meeting place for the Arab diaspora, and she also made friends with key figures in the Los Angeles art scene, such as Sam Francis and Ed Moses, whom she often painted.

By that time, one of Caland’s sons was living in Los Angeles, as well as her daughter, Brigitte. Brigitte describes Caland as painting on the walls and the floors, making work even while hosting others, and giving away many of her works to fellow artists and friends. The studio in Venice is still there; she left only in 2013, when she became ill and returned to Beirut.

Following a common pattern for women artists, at the end of her life Caland’s work was beginning to be explored by curators and institutions. A show in 2015 at the Beirut Art Center brought focus to her work again in the region, and the Sharjah Art Foundation, in addition to featuring her in the 2019 biennial, has recently acquired three of her works. A solo show of her work was also staged over the summer at Tate St Ives, including both her paintings and her drawings, to strong reviews in the UK press.

Caland was described as warm and generous with a quick wit — a woman who would speak her mind. “She set her own rules,” says Brigitte. Her independence was important not only to her life but also to her art. “She didn’t choose a conventional path, and she chose to think of art as a particular kind of freedom and optimism that flows into the present,” says Kholeif.

www.thenational.ae