Lone figures lost in thought – these are Edward Hopper’s most memorable subjects. The American artist, who earned his career breakthrough in the mid-1920s and 1930s after decades of obscurity, is known for his enigmatic and melancholic paintings of urban life.

His most famous work, Nighthawks (1942), continues to be referenced and replicated in popular culture today. In a brightly lit diner, three customers sit, slightly apart, without acknowledging each other, each one wearily preoccupied with their own problems.

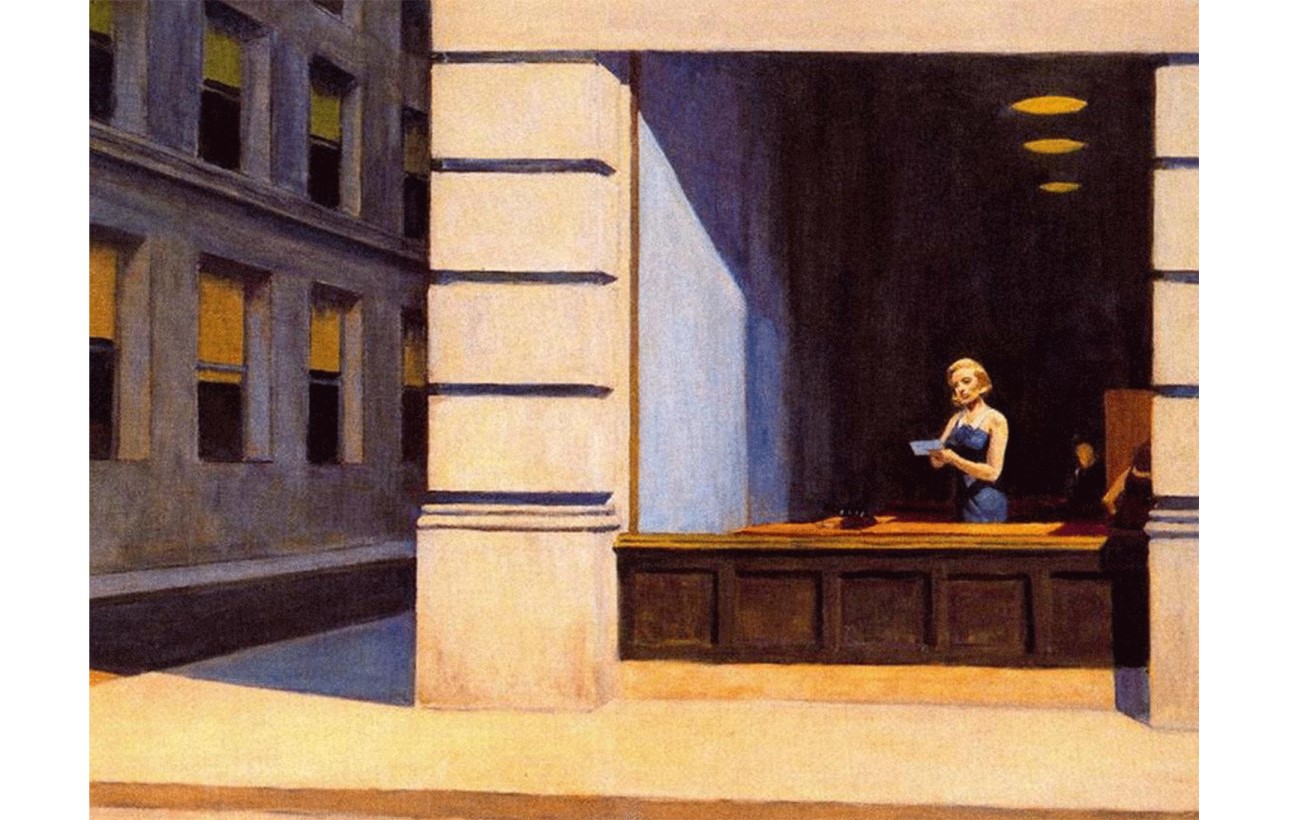

It exemplifies Hopper’s style – a dramatic play of light and shadow, cinematic composition, and an air of mystery.

Tensions and disconnections between people, especially couples, repeat in paintings such as Room in New York and Summer Evening.

Often, Hopper portrays individuals caught up in unknown anxieties or loneliness, as in Automat, where a woman hunches over a table with a cup of coffee. The blackened window reveals that it is dark outside, and her layers of clothing indicate that she might be taking shelter from the cold.

“We are all Edward Hopper paintings now,” wrote a user on Twitter, alluding to the sense of isolation that has permeated societies undergoing lockdown due to the coronavirus pandemic. It seemed to resonate – at least 200,000 people liked the tweet. As of Tuesday, nearly a billion people were in lockdown as governments call for social distancing to stem the spread of the disease.

These painterly expressions of loneliness may indeed mirror what so many of us feel inside as of late, but Hopper’s works are more than just their melancholic moods. They are, in fact, brilliant psychological portraits that speak to the artist’s own experience and outlook on life.

Hopper’s life

Born in 1882 in the shipbuilding town of Nyack, New York, he grew up in a middle-class family. Showing artistic promise at a young age, his parents fostered his skills, but pushed him towards commercial illustration rather than fine art. He began working at an advertising agency in 1905, but felt deeply unsatisfied with his work.

Looking to escape, he took trips to Europe and spent time in Paris, where he was influenced by Impressionist painters Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas. Hopper was drawn to their depictions of daily life. His time in Paris coincided with the rise of Cubism and Fauvism, spearheaded by the likes of Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse.

Yet Hopper clung to his realist style, and claimed not to remember Picasso’s name. Even then, he was an outsider. While his contemporaries may have taken up the free-spirited bohemian lifestyle, he preferred to explore the city and contemplate on its narrow streets and architectural elements, as seen in his work.

After moving back to the US in 1910, Hopper moved to Greenwich Village in New York City, and eventually returned to commercial illustration to make a living. Though he sold a painting at the Armory Show in 1911, he did not sell another artwork for 11 years. Still, he continued to create, producing dark etchings that preluded the film noir aesthetic of the 1940s.

His marriage to Josephine Verstille Nivison in 1924 was a turning point in his life. She became his muse, posing for his paintings and encouraging his artistic practice. The two shared a strong, tumultuous relationship and often ventured to Cape Cod, Massachusetts, the seaside landscapes of which became a big part of his later paintings.

Hopper’s prominence as an artist took hold, leading to exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art and participation at the 1952 Venice Biennale. By the time of his death in 1967, he was regarded as a major artist in America.

Why so many feel connected to his work, decades on

Decades later, how does his work continue to reverberate? His canvasses certainly referred to concerns from his own era, with the gloomy cloud of war hanging over the US in the 1940s and the rapid rise of urbanisation that cultivated anomie in cities. In their solitude and social isolation, Hopper’s figures offer a kinship to the viewer, a recognition of the fleeting moments of loneliness that exist in all of us – whether we’re in the midst of a pandemic, economic recession or just an ordinary day.

More importantly, a Hopper painting demands something from us – a story or an interpretation. Typically, his urban settings feature transient hubs, such as motels, train stations and cafes, places far from home and a sense of security.

His works read like book covers, like scenes from movies. They await narrative. This mix of mystery and openness is what makes Hopper’s paintings so exquisite and memorable – and seeing them through lens of a pandemic still seems somehow apt.

Though Hopper is not usually recognised as a highly technical painter, his process was incredibly deliberate. He pored over images for research and tore through sketches to arrive at his final piece. Each stroke on the canvas was a careful gesture. The contrast of light in his works may be defined such in the forlorn New York Movie, but the figures in them are typically rendered in soft strokes and their facial features are hardly ever sharp, adding a sense of anonymity and mystery.

By looking at Hopper’s works, we see our own existence in his subjects. Hopper seeks not to compound our loneliness, but simply to recognise it.

www.thenational.ae