On July 6, Paris’ Musée du Louvre — the world’s most-visited museum — will reopen after shutting its doors on March 13 in response to the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Museumgoers are required to book entry tickets online in advance and wear masks at all times inside the Louvre. To mark the reopening, Arab News takes a closer look at five ancient artworks from the museum’s collection inspired by, or hailing from, the Arab world.

The oldest work on display at the Louvre comes all the way from the Levant. This extremely delicate and noticeably cracked depiction of an armless human form is 9,000 years old and considered by scholars to be one of the earliest representations of a human being. This gypsum statue was discovered in the 1980s through rescue excavations at a Neolithic archaeological site and former farming village — known as Ain Ghazal or ‘Spring of the Gazelle’ — near Amman, Jordan. The function of such an effigy remains a mystery, however it was probably used to honor the communities’ ancestors. Today, approximately 30 of these Ain Ghazal statues have been recovered and are housed in The Jordan Museum, The British Museum, and Louvre Abu Dhabi.

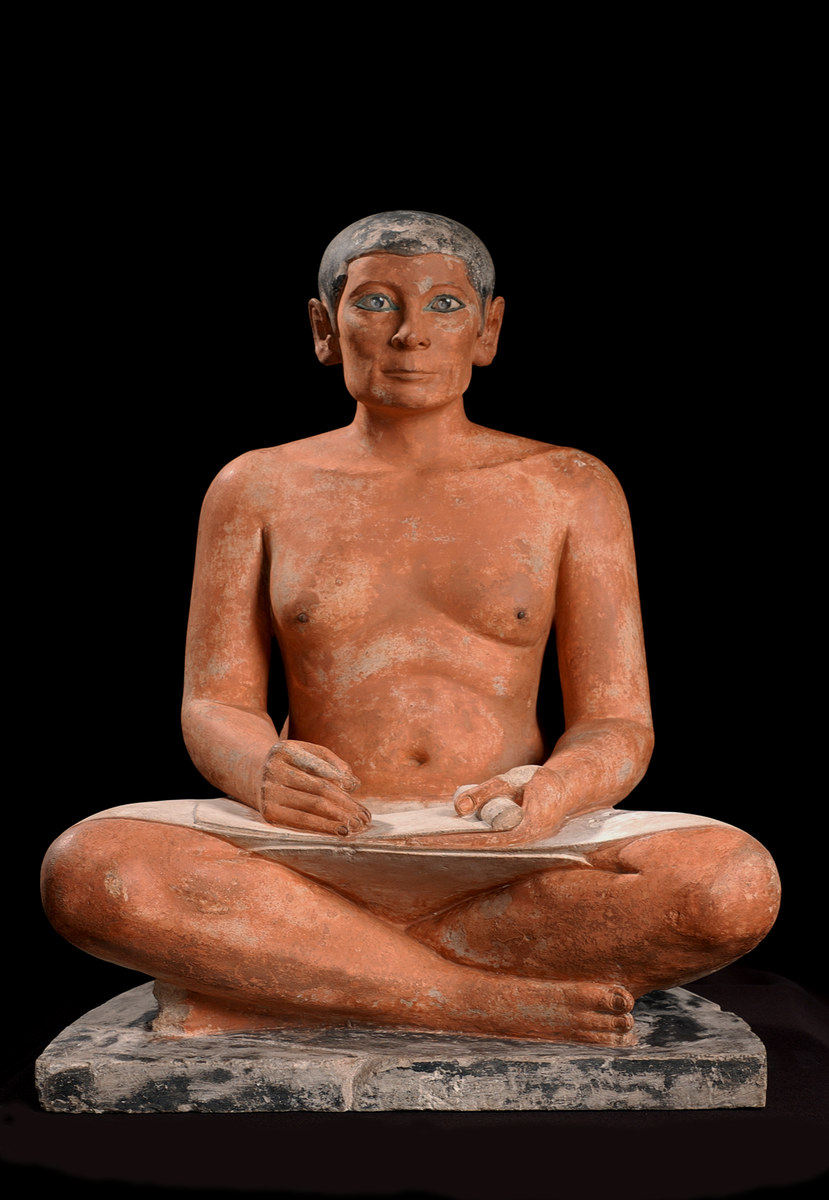

‘The Seated Scribe’

This lifelike Ancient Egyptian statue depicts a cross-legged scribe in white kilt equipped with a rolled papyrus scroll. Scribes were highly regarded at a time when the majority of people were unable to read or write, and played an important role in society. The famous ancient document Papyrus Lansing highlighted this, saying, “Writing, for him who knows it, is better than all other professions. It is worth more than an inheritance in Egypt, than a tomb in the west.” It’s worth remembering, however, that Papyrus Lansing was written by a scribe.

The terracotta-toned, painted limestone “Seated Scribe” reportedly dates back to Egypt’s Fourth or Fifth dynasty and was found in Saqqara, a massive burial ground in the Egyptian city of Memphis. The remarkable presentation of the scribe’s thickly contoured and polished rock crystal eyes has drawn particular attention from experts.

‘Code of Hammurabi’

This imposing basalt stele, discovered in 1901, is one of the world’s oldest examples of a legal ‘document.’ It is believed to have listed 282 laws — as well as the punishments incurred for breaking them — enacted by Hammurabi, the sixth Babylonian king, in the 17th century BCE (predating Biblical laws). Only around 30 laws have been deciphered, and many had been scraped off by the time the code was found. The monument describes the king as “protector of the weak and oppressed” and lays out laws concerning agriculture, slavery, crime, and family — the longest section of them all.

The laws were written in the Akkadian language, using wedge-shaped cuneiform script. A scene on the upper part of the stele — which stands over two meters tall — depicts the king and the sun god Shamash.

‘Pyxis of Al-Mughira’

This cylindrical box — known as a pyxis — was created in Arab-ruled Spain, probably in Cordoba, in the 10th century. Made of elephant ivory, the pyxis is intricately carved from top to bottom, revealing a band of Arabic calligraphy and depictions of exotic wild animals and various princely figures.

It was a gift for Prince al-Mughira, the youngest son of the Ummayad ruler Abd al-Rahman III, who was expected to consolidate Ummayad power over the Abbasids. So this pyxis has a political undertone with its four medallions that symbolize Ummayad legitimacy. We see, for example, a pair of lions (representing Ummayad sovereigns) digging their teeth into enemy bulls.

‘Door leaf from the Dar Al-Khalifa palace in Samarra’

This unique specimen of an ornamentally carved door made of teak imported from India was taken from the Dar al-Khalifa Palace, commissioned by Abbasid leader Al-Mu’tasim and situated in the ancient city of Samarra, Iraq —famed for its spiral minaret and for being the second capital (after Baghdad) of the Abbasid Caliphate.

Divided into three vertical panels, the door shows a simple five-lobed leaf topped with a fan-like motif. Curators have speculated that this door was likely used for an important entrance, given its height of almost two-and-a-half meters.

arabnews